The issue of Digital assets has come up again in the mainstream press. It was covered on the CBC in Canada and then was picked up by media outlets around the World. The Washington post ran with the headline

Her dying husband left her the house and the car, but he forgot the Apple password

The Daily Mail in the UK also ran the story with the headline “Widow who wanted her dead husband’s Apple ID so she could play games on their iPad is refused and told to get a COURT order instead”. The Sydney Morning Herald also alerted its readers. Google news is claiming 19,000 separate news articles about Peggy Bush, the 72 year old Canadian widow who simply wanted to play some games on the family iPad. The card game stopped working so she wanted to update it. To do this, she needed her late husband’s Apple ID password.

Copyright: fgnopporn / 123RF Stock Photo

The best option that Apple gave her was to create a new Apple ID, but this would mean re-purchasing all of the games that had already been purchased by her husband. There was no way of transferring the games from one Apple ID account to another.

Apple suggested that they would only be able to release the User ID and password of the account with a court order. The general reaction was that this was a little unsympathetic to the situation; all of Peggy’s late husband’s assets had been successfully transferred, and nobody, including banks and insurance companies, had required a court order to do this.

Why digital assets?

These stories are fascinating because there is no consistent legislation in place to handle digital assets. It is left up to companies to create their own procedures, and many companies deal with this issue on a case-by-case basis. We are guilty of this at USLegalWills.com where every day we speak to family members trying to work through an estate, and the first step is trying to locate a Last Will and Testament.

We don’t like to be heavy-handed or insensitive, and when you are dealing with a grieving widow over the phone who wants to know if her husband has documented any of their wishes. It is very difficult to “do an Apple” and insist on a court order.

The process for transferring ownership of a car or house is quite well documented. But the process for transferring the balance of a PartyPoker account, or a photo-library of Google Photos, or a family tree on Ancestry.com, is inconsistent at best.

What exactly are digital assets?

Let’s start with what they are not. Having online access to a bank account, does not make your bank account a digital asset. In the context of estate planning, digital assets are items that exist online that have sentimental or financial value. But also accounts that just need to be managed that really have no intrinsic value. There are broadly three classes of digital asset;

Accounts that need to be managed for housekeeping

We all now have countless online accounts, and for most of these it makes sense for somebody to take responsibility to close them down. I personally have 3 LinkedIn contacts who have died. Once a year, I am prompted to congratulate them on their work anniversary. It’s sad, disrespectful and distasteful. Most online services have processes in place for the closing of an account, but it’s a good idea to make somebody aware that the accounts exist. In most cases it makes sense for your Executor to take responsibility for going through the process of administering these accounts:

Accounts that have sentimental value

These need to have a beneficiary defined in order to avoid family disputes. They can include family photograph collections, memoirs collected in a blog, family trees developed at Ancestry.com or even virtual worlds. Some of these online collections have taken years of effort to develop and somebody should maintain them, or at least download them. There is no way to directly transfer a Flickr account for example, to another Flickr account. So all of the photos need to be downloaded and then potentially uploaded to a new account.

Just supposing family members don’t get along. What happens when one family member takes it upon themselves to access the family photos or even close the account down, before the other family members have had a chance to react? These are digital assets which are every bit as emotionally valuable as a porcelain teapot.

Accounts that may have monetary value

These are digital assets that have serious estate planning consequences. Although they are “digital assets” they have real value in the real World. These include things like ad revenues from blogs or YouTube videos, online gambling accounts, and even virtual currency.

One of the intriguing examples though is the area of domain names. We know that domain names trade for very large sums of money, but nobody technically “owns” a domain name. They are all effectively leased.

If you were to own “toys.com” and then passed away. If nobody does anything with that domain, it will become available to the first person to grab it for about $10. If a member of your family, or digital executor were to transfer it, and then sell it, it would easily be worth over $100,000.

Your Last Will and Testament should have a plan for digital assets like domain names.

The blurred lines between these

There is a growing grey zone between emotionally valuable digital assets and those with financial value. Particularly in the area of vanity or prestige “handles” that were grabbed by early adopters of new services like Twitter handles and account names for things like Skype or Gmail.

It is only a matter of time before we see loved ones fighting each other for the Pinterest ID of “savvymom” or the gmail account of [email protected]. Technically many services do not permit the transfer of a user ID, but it would be easy for a loved on to assume an ID, particularly if there was some prestige associated with it.

There are digital assets that we have never heard of; the next Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, Instagram, and the early users of the new services will be grabbing the most prestigious user names. These will then become digital assets.

What about other accounts?

There was a recent article in the Canadian media addressing the issue of the transfer of airmiles. A woman died with 250,000 Aeroplan points and the family wanted them transferred to her husband. Aeroplan demanded the payment of a $2,500 administration fee, resulting in a social media backlash. The interesting twist though is that Aeroplan are actually one of the very few loyalty programs that would facilitate this at all…even with a fee. We did a quick check of the major loyalty programs in the US, and couldn’t find a single one that would transfer points to a beneficiary.

Rewards Certificates and Perk Certificates are not transferable and may not be combined among Members or conveyed by any means to anyone, including through a Member’s estate, and may not pass to a Member’s successors and assigns. Rewards Certificates and Perk Certificates do not constitute property of the Member. Accrued Points, accrued Perk Purchases, Rewards Certificates and/or Perk Certificates are not transferable by the Member upon death

In March 2013, Delta Airlines changed its policy, declaring SkyMiles would no longer be transferable upon death. And BestBuy Rewards have the standard “no transfer” policy

Reward certificates are not transferable and may be used only by the member to whom issued.

Death without a digital executor

For more traditional assets like bank accounts, the process is well established. Your Executor presents your Last Will and Testament to the probate courts. The courts then issue a “grant of administration” which is used by your Executor to gather your assets. This document is accepted by the banks to release the contents of an account, confident that the person requesting the asset is the court appointed Executor.

Even though online services have processes, they have no way of knowing who has the authority to act on an account.

The system generally relies on loved ones having the User ID and password of an account, so they can take the appropriate action of collecting the digital assts or closing the account.

Twenty years ago, loved ones went through the filing cabinet of a loved one to make sense of an estate. Today, the “golden key” is access to the deceased’s main email account.

But without a designated digital Executor it is easy for family members to be treading on each other’s toes to reassign ID’s, close down accounts, and transfer digital assets. Facebook for example have an option to memorialize an account. Who will be making the decision to do this? a spouse? a child? a parent?

Do you want your passwords to be shared?

Simply giving your password to a loved one is not a strategy. Giving your master password for a service like LastPass or Dashlane will provide unfettered access to your digital world for your loved ones, but it’s rather wide reaching.

Copyright: antonioguillem / 123RF Stock Photo

There is an obvious shortcoming of this approach.

You may not want every digital asset to be known to your loved ones. They may be embarrassing or secret accounts that should die with you. These include online dating profiles, online help for personal issues, order history for private goods, personal correspondence, diaries, medical histories or treatments.

There are perfectly reasonable reasons for not wanting every part of your life in the hands of a spouse or child.

In addition, it’s important that a master password gets into the hands of the people who need it at the appropriate time, and not before. The consequences can be catastrophic.

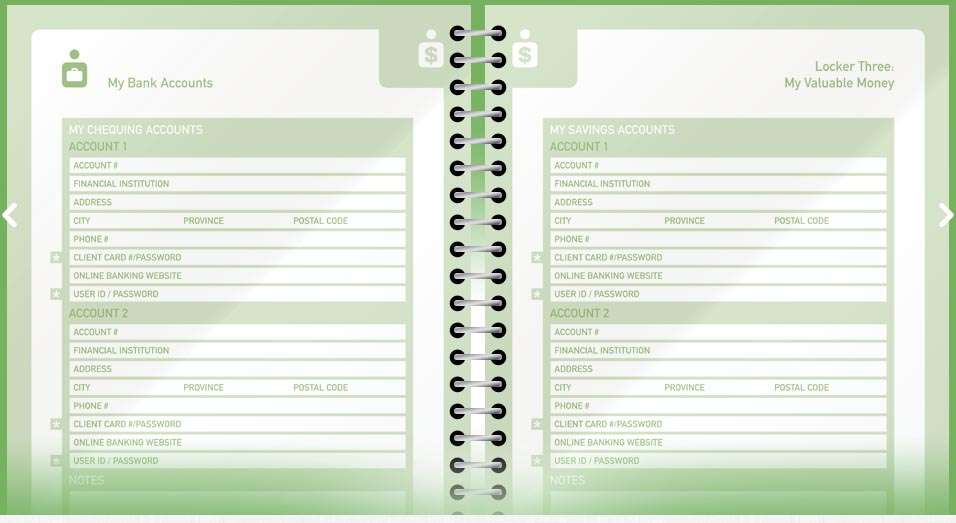

Documenting all of your assets and wishes

The issue of course goes beyond digital assets. This is why we have partnered with MyLifeLocker to allow you to create a complete compendium of your online and offline life. It has now become the ultimate tool for your Executor.

The single most difficult task for your Executor will be to gather your assets. If these are not documented anywhere, the task is never ending. According to a recent survey around 7 percent of Americans admitted to having a bank account that was secret from their spouse. It is even more likely that there is some money or an account that is not known by your Executor.

To avoid this asset going into the black hole of unclaimed accounts (There is currently $42 billion in unclaimed funds floating around in the United States, according to the National Association of Unclaimed Property Administrators (NAUPA). You should document these assets in a tool like MyLifeLocker.

One quick note on the listing of assets that is commonly misunderstood. You do not want to include all of this information in the actual Last Will and Testament for two important reasons:

You are not writing your Will because you think you are going to die today. Your Will is not likely to come into effect for many years into the future. You do not want to have to update your Will every time an asset changes as this would require stepping through the formal signing procedure every time.

Furthermore, once your Will goes through the probate process, it becomes a public document. Anybody and everybody can read it. There are some assets that you may want to keep shielded from the eyes of the World, and you most certainly do not want to include your login credentials for your online accounts in a public document.

But I’m not going to die any time soon

Many new businesses have been set up to address the challenge associated with digital assets, but they are invariably flawed in that they require you to pay an ongoing subscription. The service then kicks in and offers value once you die.

This means that all the time you are paying your monthly subscription and staying alive, you are getting very little value out of the service.

It also requires that the silicon valley startup outlives you….statistically, not likely.

One other note about these services; they often claim to let you upload your Will to their server for easy access. An uploaded Last Will and Testament would not be a legal document, so it would actually be useless if your Executor tried to use it.

It is a good idea to create your LifeLocker (or equivalent service) today, and then update it throughout your life. But it’s difficult to justify a monthly subscription to a service when you are probably not going to die for another 30+ years.

Fortunately, we offer a one-time lifetime subscription option which not only allows you to update your LifeLocker throughout your life, but also your Last Will and Testament and other estate planning documents.

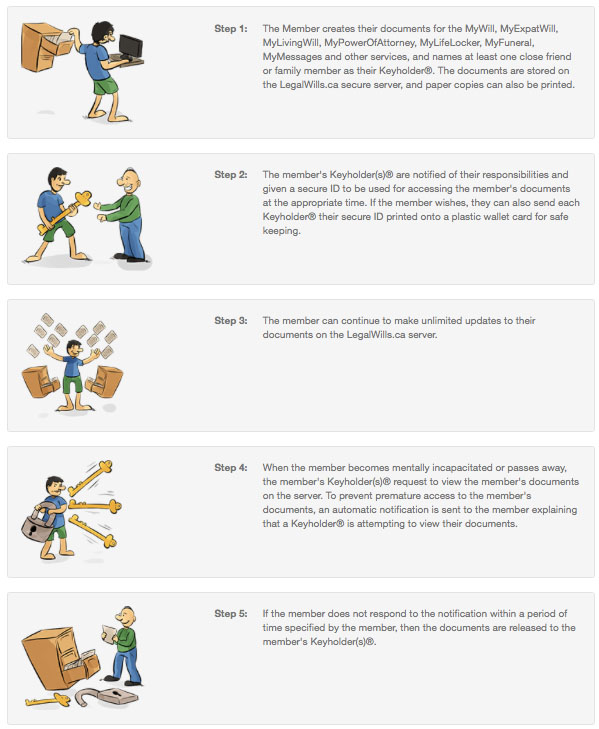

LifeLocker and the keyholder

Once you have met the challenge of documenting your digital assets, and keeping them updated, you need to make sure that they are available to the right people at the right time. And not before that.

At USLegalWills.com we have addressed this with our Keyholder™ mechanism. You name trusted keyholder and give them access to services within your account at USLegalWills.com. They can then unlock these documents, which are then published after a safety timer has expired. The detailed flow is explained in the following graphic.

Using our Keyholder™ service insures that your user ID’s and passwords are made available to specific people only when they need them. But are entirely private and secure throughout your life.

Bear in mind that it may not only be after you pass away. But there may be key information in your LifeLocker that would be useful to somebody with a financial Power of Attorney document if you are ever incapacitated or in a coma.

Digital Executor laws in the US

There is a growing recognition of the role of a “Digital Executor”. Most people are familiar with the roles and responsibilities of a traditional estate Executor, who gathers assets, files taxes and arranges a funeral. But the person most adept and handling this paperwork, may not be the most qualified to conduct an online account audit. It is also important to note that there is no legal appointment for somebody to take over your Flickr account, so it is unclear at this point what happens in a family dispute over a Twitter handle for example.

Recently the Uniform Law Commission passed the Fiduciary Access to Digital Assets Act. The ULC creates suggestions in the hope that individual States will adopt their recommendations. In this case, the Fiduciary Access to Digital Assets Act recommends that a Digital Executor should be granted access to an online account irrespective of the individual site’s Terms of Service.

There are clearly privacy concerns with this, but it makes sense to grant some legal authority to a digital Executor. Most companies are not equipped to deal with bickering loved ones fighting over a digital domain.

The Digital Beyond recently calculated that almost one million Facebook users in the US will die in 2016.

But States are slow to adopt digital executor laws. By our most recent review, only Connecticut, Delaware, Idaho, Indiana, Maine, Maryland, Michigan, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Virginia have any digital estate laws in place.

The steps you should take right now

Firstly, we would recommend that you prepare your estate planning documents using a service like ours at USLegalWills.com. You should have at least a Last Will and Testament no matter how old you are. You should also consider a Financial Power of Attorney and a Living Will (Healthcare Power of Attorney).

The next step is to document your assets including your digital assets using MyLifeLocker at USLegalWills.com.

The final step is to designate trusted keyholders who can access this important document at the appropriate time.

We have a dedicated support team who can help you through this process. If you have any questions, then please feel free to leave a comment.

- Testamentary Trusts – what are they and how are they created? - May 9, 2024

- Every document you need for a complete estate plan. - October 29, 2020

- Estate Planning in troubled times - April 3, 2020